INTRODUCTION

The Supreme Court of India is the highest judicial court and the final court of appeal under the Constitution of India, the highest constitutional court, with the power of judicial review. Consisting of the Chief Justice of India and a maximum of 31 judges, it has extensive powers in the form of original, appellate and advisory jurisdictions.[

As the final court of appeal of the country, it takes up appeals primarily against verdicts of the high courts of various states of the Union and other courts and regions. It protects fundamental rights of citizens and settles disputes between various government authorities as well as the central government vs state governments or state governments versus another state government in the country. As an advisory court, it hears matters which may specifically be referred to it under the constitution by President of India. It also may take cognisance of matters on its own (or suo moto), without anyone drawing its attention to them. The law declared by the supreme court becomes binding on all courts within India and also by the union and state governments. Per Article 142 of the constitution, it is the duty of the president to enforce the decrees of the supreme court.

History

In 1861 the Indian High Courts Act 1861 was enacted to create high courts for various provinces and abolished supreme courts at Calcutta, Madras and Bombay and also the sadr adalats in presidency towns which had acted as the highest court in their respective regions. These new high courts had the distinction of being the highest courts for all cases till the creation of Federal Court of India under the Government of India Act 1935. The Federal Court had jurisdiction to solve disputes between provinces and federal states and hear appeal against judgements of the high courts. The first CJI of India was H. J. Kania.[

The Supreme Court of India came into being on 28 January 1950. It replaced both the Federal Court of India and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council which were then at the apex of the Indian court system. The first proceedings and inauguration, however took place on 28 January 1950, at 9.45 a.m, when the judges took their seats, and thus regarded as the official date of establishment.

Supreme court initially had its seat at Chamber of Princes in the parliament building where the previous Federal Court of India sat from 1937 to 1950. The first Chief Justice of India was H. J. Kania. In 1958, the supreme court moved to its present premises. Originally, the Constitution of India envisaged a supreme court with a chief justice and seven judges; leaving it to parliament to increase this number. In formative years, the supreme court met from 10 to 12 in the morning and then 2 to 4 in the afternoon for 28 days in a month.

Appointments and the Collegium

As per the constitution, as held by the court in the Three Judges Cases – (1982, 1993, 1998), a judge is appointed to the supreme court by the president on the recommendation of the collegium — a closed group of the Chief Justice of India, the four most senior judges of the court and the senior-most judge hailing from the high court of a prospective appointee.[ This has resulted in a Memorandum of Procedure being followed, for the appointments.

Judges used to be appointed by the president on the advice of the union cabinet. After 1993 (the Second Judges’ Case), no minister, or even the executive collectively, can suggest any names to the president, who ultimately decides on appointing them from a list of names recommended only by the collegium of the judiciary. Simultaneously, as held in that judgment, the executive was given the power to reject a recommended name. However, according to some, the executive has not been diligent in using this power to reject the names of bad candidates recommended by the judiciary.

The collegium system has come under a fair amount of criticism. In 2015, the parliament passed a law to replace the collegium with a National Judicial Appointments Commission(NJAC). This was struck down as unconstitutional by the supreme court, in the Fourth Judges’ Case, as the new system would undermine the independence of the judiciary.Putting the old system of the collegium back, the court invited suggestions, even from the general public, on how to improve the collegium system, broadly along the lines of – setting up an eligibility criteria for appointments, a permanent secretariat to help the collegium sift through material on potential candidates, infusing more transparency into the selection process, grievance redressal and any other suggestion not in these four categories, like transfer of judges. This resulted in the court asking the government and the collegium to finalize the memorandum of procedure incorporating the above.

Once, in 2009, the recommendation for the appointment of a judge of a high court made by the collegium of that court, had come to be challenged in the supreme court. The court held that who could become a judge was a matter of fact, and any person had a right to question it. But who should become a judge was a matter of opinion and could not be questioned. As long as an effective consultation took place within a collegium in arriving at that opinion, the content or material placed before it to form the opinion could not be called for scrutiny in court.[

Tenure

Supreme court judges retire at the age of 65. However, there have been suggestions from the judges of the Supreme Court of India to provide for a fixed term for the judges including the Chief Justice of India.

Salary

Article 125 of the Indian constitution leaves it to the Indian parliament to determine the salary, other allowances, leave of absence, pension, etc. of the supreme court judges. However, the parliament cannot alter any of these privileges and rights to the judge’s disadvantage after his/her appointment.[ A judge of the supreme court draws a salary of ₹250,000 (US$3,500) per month—equivalent to the most-senior civil servant of the Indian government, Cabinet Secretary of India—while the chief justice earns ₹280,000 (US$3,900) per month.

Oath of affirmation

As Per Article 124 and third Schedule of the constitution, the chief justice (or a judge) of the Supreme Court of India is required to make and subscribe in the presence of the president an oath or affirmation that he/she

will bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India as by law established, that I will uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India, that I will duly and faithfully and to the best of my ability, knowledge and judgement perform the duties of my office without fear or favour, affection or ill-will and that I will uphold the Constitution and the laws.

Removal

Per Article 124(4) of the constitution, President can remove a judge on proved misbehaviour or incapacity when parliament approves with a majority of the total membership of each house in favour of impeachment and not less than two thirds of the members of each house present. For initiating impeachment proceedings against a judge, at least 50 members of Rajya Sabha or 100 members of Lok Sabha shall issue the notice as per Judges (Inquiry) Act,1968. Then a judicial committee would be formed to frame charges against the judge, to conduct the fair trial and to submit its report to parliament. When the judicial committee report finds the judge guilty of misbehaviour or incapacity, further removal proceedings would be taken up by the parliament if the judge is not resigning himself

The judge upon proven guilty is also liable for punishment as per applicable laws or for contempt of the constitution by breaching the oath under disrespecting constitution

Post-retirement

A Person who has retired as a judge of the supreme court is debarred from practicing in any court of law or before any other authority in India.

Review petition

Article 137 of the Constitution of India lays down provision for the power of the supreme court to review its own judgements. As per this Article, subject to the provisions of any law made by parliament or any rules made under Article 145, the supreme court shall have power to review any judgment pronounced or order made by it.

Under Order XL of the supreme court Rules, that have been framed under its powers under Article 145 of the constitution, the supreme court may review its judgment or order but no application for review is to be entertained in a civil proceeding except on the grounds mentioned in Order XLVII, Rule 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

Powers to punish for contempt

Under Articles 129 and 142 of the constitution the supreme court has been vested with power to punish anyone for contempt of any court in India including itself. The supreme court performed an unprecedented action when it directed a sitting minister of state in Maharashtra government, Swaroop Singh Naik, to be jailed for 1-month on a charge of contempt of court on 12 May 2006.

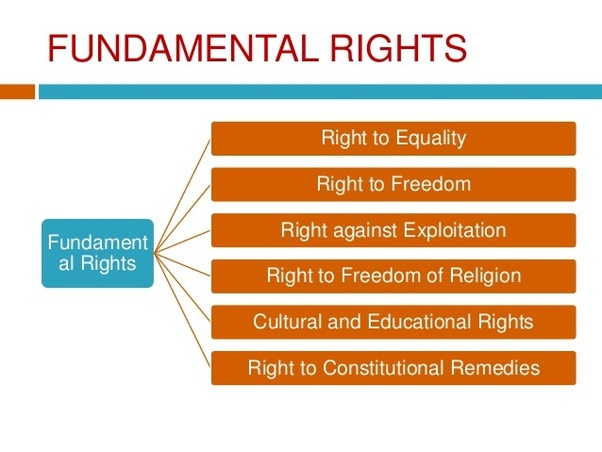

Supreme Court as Guardian of Fundamental Rights

As the protector and guardian of fundamental rights, from the very beginning the Supreme Court has adopted the stance that it acts as the ‘sentinel on the qui vive’ vis-a-vis fundamental rights and has stressed this role in several cases. The Constitution underlines this role of the court through article 32(1), which reads: The Supreme Court shall have power to issue directions or orders or writs, including writs in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto and certiorari, whichever may be appropriate, for the enforcement of any of the rights conferred by this article. The Constitution-makers made the right of a citizen to move the Supreme Court under article 32, and claim an appropriate writ against the unconstitutional infringement of his fundamental rights, itself a fundamental right. Commenting on this role entrusted to itself, the court observed in Daryao v State of Uttar Pradesh: The fundamental rights are intended not only to protect individual’s rights but they are based on high public policy. Liberty of the individual and the protection of his fundamental rights are the very essence of the democratic wav of life adopted by the Constitution, and it is the privilege and the duty of this Court to uphold those rights. This Court would naturally refuse to circumscribe them or to curtail them except as provided by the Constitution itself.4 In the very first year of the Constitution coming into force, the Supreme Court emphasized in Romesh Thappar v State of Madras,5 that ‘this Court is thus constituted the protector and guarantor of the fundamental rights, and it cannot, consistently with the responsibility so laid upon it, refuse to entertain applications seeking protection against infringement of such rights.’ The protective role of the Supreme Court, has in course of time manifested itself in the following ways, namely (a) declaration of a law as unconstitutional in case it comes in conflict with a fundamental right; (b) prohibition on an individual from bartering away his fundamental rights; (c) non-amendability of the constitutional provisions guaranteeing fundamental rights; (d) protection of its own protective function from being demented either by legislation or constitutional amendment. A few words need be said to explain each of these aspects.

Waiver of Fundamental Rights

Early in the day, the Supreme Court was faced with the question: can a person waive any of his fundamental rights? To begin with, Venkatarama Ayyar, J, in Behram v State of Bombay,” divided the fundamental rights into two broad categories: rights conferring benefits on individuals, and rights conferring benefits on the general public. The judge opined that a law would not be a nullity but merely unenforceable if it was repugnant with a fundamental right in the former category, and that the affected individual could waive such an unconstitutionality, in which case the law would apply to him. For example, the right guaranteed under article 19(l)(f) was for the benefit of property-owners. When a law was found to infringe this provision it was open to any person whose right had been infringed to waive his fundamental right.12 In case of such a waiver, the law in question could be enforced against the individual concerned. The majority on the bench, however, repudiated this view, holding that the fundamental rights were not put in the Constitution merely for individual benefit. These rights were there as a matter of public policy and, therefore, the doctrine of waiver could have no application in case of fundamental rights. A citizen could not invite discrimination by telling the State ‘you can discriminate’, or get convicted by waiving the protection given to him under articles 20 and 21. 1 3 Waiver of fundamental rights was discussed more fully by the court in Basheshar Natb v Income-tax Commissioner.1 * The case was referred to the Income-Tax Investigation Commission under section 5(1) of the relevant Act. After the commission had decided upon the amount of concealed income, the petitioner agreed on 5 September 1954, as a settlement, to pay in monthly instalments over Rs 3 lak by way of tax and penalty. In 1955, the court declared section 5(1) ultra vires article 14. The petitioner thereupon challenged the settlement between him and the commission, but the plea of waiver was raised’ against him. The court upheld the petitioner’s contention, but in their judgements the judges expounded several views regarding waiver of fundamental rights: 1. Article 14 cannot be waived, it being an admonition to the State as a matter of public policy with a view to implement its object of ensuring equality. No person can, therefore, by act or conduct, relieve the State of the solemn obligation imposed on it by the Constitution. 2. A view, somewhat broader than the first, was that none of the fundamental rights can be waived by any person. The fundamental rights are mandatory on the State and no citizen can by his act or conduct relieve the State of the solemn

Muslim Law

The contribution of the Supreme Court to the development of Muslim Law over the five decades of its existence has not been negligible. This contribution might have been even greater had there been a more sensitive relationship between the judges of the court (and the counsel advising it) and significant sections of Islamic scholars and progressive thinkers, as well as with Parliament. The unnatural ascendancy of arch-conservative diehafds among the Muslim politicians has created problems for everybody.1 This ascendancy came to a head during the protest over Shah Bano2 which will be dealt with presendy. Over-enthusiasm among some lawyers and judges, for early implementation of the constitutional directive for a common civil code, has also sometimes complicated the issue. There has been engendered, perhaps undeservedly, the feeling among certain ulema and their supporters, that their cherished institutions have not been adequately appreciated by the legal fraternity at large. This has obstructed the mental process of such elements and warped their appreciation of the wise, and sometimes admirable, pronouncements of certain judges and lawyers. It is a paradox that while the Muslim world as a whole has been moving forward to a far-reaching reformation,3 such reformation has barely touched the fringes of Muslim Law in India. Partly, this is on account of ill-educated moulvis and, partly, insensitivity and ignorance among the bulk of the lawyers and judges regarding the real needs and aspirations of the Muslim people. Nevertheless, important issues have been settled by the courts and significant progress has been made. This is evident from the law reports. On the whole, it may be said that the courts, and in particular the Supreme Court, have succeeded in maintaining the traditional view of Muslim Personal Law, occasionally (too rarely) ventilating its ancient and hallowed archives with much-needed currents of fresh air from contemporary life. This author wrote elsewhere regarding Muslim Law that ‘the Tomes of the Law are Grey but the Tree of Life is Green’.4 Development of closer rapport between the judges and lawyers serving the highest court in the land and enlightened elements among a sensitive minority like the Indian Muslims, conformably to the Indian concept of secularism, requires the greatest clarity of mind, erudition and goodwill on both sides. There must be the fullest trust engendered in the minority group that the court has no desire to ride roughshod over its cherished institutions.

- The Election Laws (Amendment) Bill, 2016

- was introduced in Lok Sabha by the Minister for Law and Justice, Mr. D. V. Sadananda Gowda, on February 24, 2016. It seeks to amend the Representation of the People Act, 1950 and the Delimitation Act, 2002. These Acts regulate allocation of seats to the national and state legislatures, and delimitation (i.e., fixing boundaries) of parliamentary and assembly constituencies.

- According to the Statement of Objects and Reasons, the Bills aims to empower the Election Commission to carry out delimitation in areas that were affected by the enactment of the Constitution (100th Amendment) Act, 2015. Under the 2015 Act, enclaves were exchanged between India and Bangladesh. Enclaves are territories belonging to one country that are entirely surrounded by another country. India transferred 111 enclaves to Bangladesh, and received 51 enclaves from Bangladesh on July 31, 2015.

- The 1950 and 2002 Acts provide the Election Commission the responsibility to maintain up-to-date delimitation orders. Delimitation orders specify the boundaries of territorial constituencies. This responsibility includes: (i) correcting printing mistakes and inadvertent errors, and (ii) making necessary amendments if the name of any territorial division mentioned in the delimitation order has been altered.

- The Bill amends the Acts in order to give additional powers and responsibilities to the Election Commission. It states that the Election Commission may amend the delimitation order to: (i) exclude from the relevant constituencies the Indian enclaves that were transferred to Bangladesh, and (ii) include in the relevant constituencies the Bangladeshi enclaves that were transferred to India.

Consumer Protection Law In India

The growing interdependence of the world economy and international character of many business practices have contributed to the development of universal emphasis on consumer rights protection and promotion. Consumers, clients and customers world over, are demanding value for money in the form of quality goods and better services. Modern technological developments have no doubt made a great impact on the quality, availability and safety of goods and services. But the fact of life is that the consumers are still victims of unscrupulous and exploitative practices. Exploitation of consumers assumes numerous forms such as adulteration of food, spurious drugs, dubious hire purchase plans, high prices, poor quality, deficient services, deceptive advertisements, hazardous products, black marketing and many more. In addition, with revolution in information technology newer kinds of challenges are thrown on the consumer like cyber crimes, plastic money etc., which affect the consumer in even bigger way. ‘Consumer is sovereign’ and ‘customer is the king’ are nothing more than myths in the present scenario particularly in the developing societies. However, it has been realized and rightly so that the Consumer protection is a socio- economic programme to be pursued by the government as well as the business as the satisfaction of the consumers is in the interest of both. In this context, the government, however, has a primary responsibility to protect the consumers’ interests and rights through appropriate policy measures, legal structure and administrative framework.

Consumers participate in the marketplace by using a particular product. Had there been no consumer no company would exist. The status of consumer is more or less pathetic as far as consumer rights are concerned. You can take examples of shopkeepers weighing less than he should, company’ making false claims on packs. Then there are local sweetmeat sellers adulterating raw materials to produce the laddoos or barfis. You can recall the case of dropsy because of adulterated mustard oil. No matter how bad quality you get, chances are you will get a rude response from the shopkeeper if you dare to complain

The Role of Indian Judiciary in Upholding Gender Justice Through Protective Discrimination: An Appraisal

The last few decades have seen a growing recognition of women’s rights as human rights and as an integral and indivisible part of universal human rights. In international law, the issue of women’s rights is emerging as one of the main slogans and rapidly developing subfield of international human rights protection. The Constitution of India recognizes the rights of working women and ensures equal rights and opportunities. There are numerous provisions which not only ensure equality before law and prohibit any discrimination on the basis of gender, but also empower the state to make special provisions for working women. Many laws have also been enacted in accordance with these Constitutional provisions and international obligations for the protection and promotion of gender justice for women. The Indian judiciary also has been playing a significant role in upholding the equal status of women. During the last decade, the Indian judiciary has recognized gender-based discrimination in favor of women, i. e., protective discrimination, and upheld its constitutionality on the basis of their peculiar conditions — physical, mental and psychological — if it protects the interests of women. This paper seeks to examine the role played by the Indian judiciary in ensuring gender justice through protective discrimination.

References

| Title: | Fifty Years of the Supreme Court of India : Its Grasp and Reach |

| Authors: | Verma, S.K. Kusum |

| Publisher: | Indian Law Institute,New Delhi |

Legalservice.com

Dr Aneesh .V PIllai, blog

Wikipedia

The Indian Law Institution